Internship

Hands-on experiences in research laboratories and virtual classrooms, where theory meets practice.

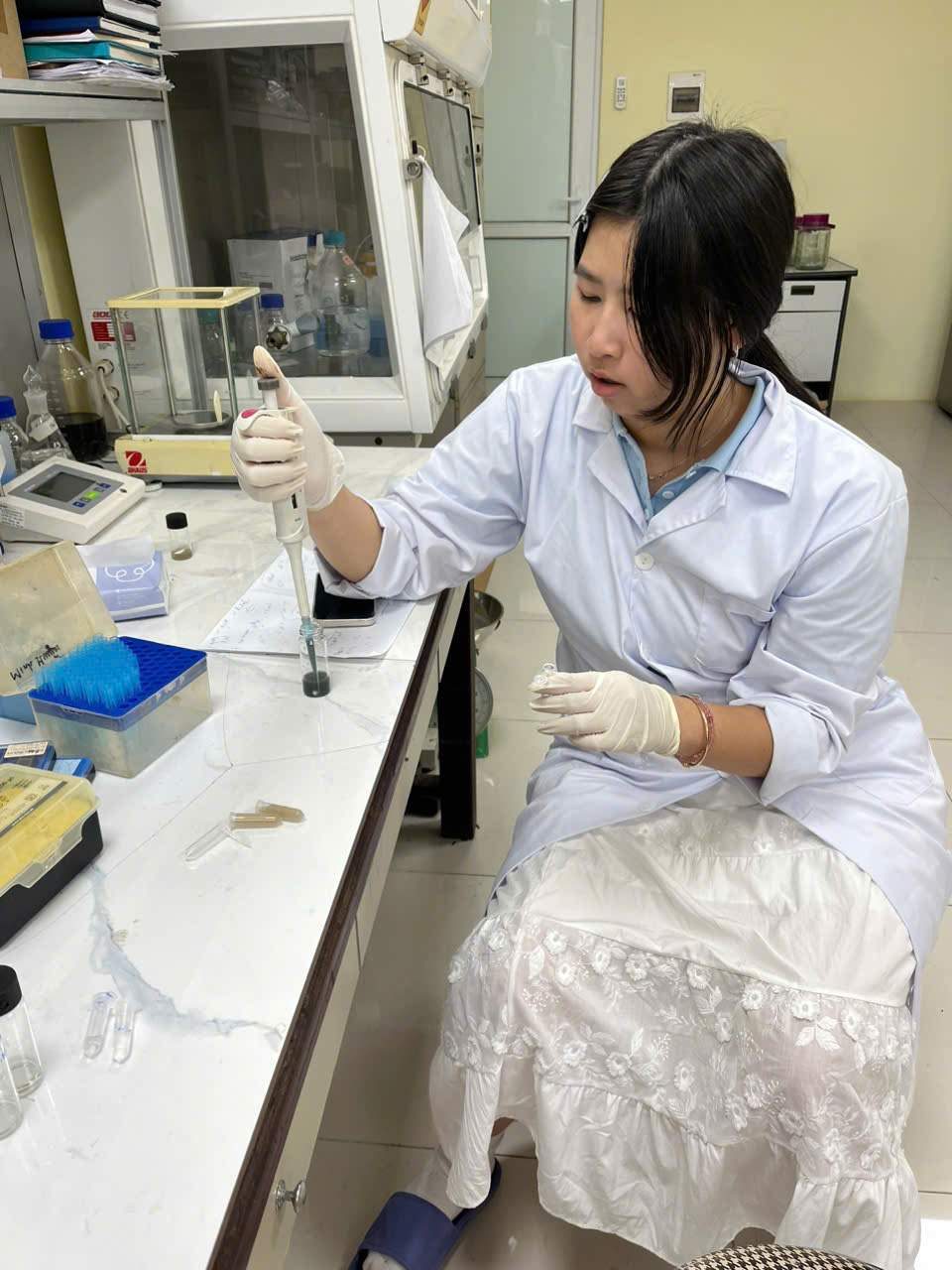

Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology

During my internship at the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, I worked on synthesizing spherical silver nanoparticles. My first attempts did not go as planned. While the teacher's model experiment produced a dark grey solution, mine turned dark green. Measuring UV-Vis absorption, particle size, zeta potential, and infrared spectra revealed why: my nanoparticles were larger than intended and clumped together more. Each reading made the chemistry visible in a way textbooks never could, showing how small variations in reactant ratios and volumes could drastically change outcomes.

Precision Instruments

What fascinated me most were the instruments themselves. Using a microbalance to weigh tiny amounts, operating the centrifuge and drying oven, and measuring optical properties with spectrophotometers introduced me to the precision real research requires. The fluorescent microscope and Raman spectrometer felt almost magical. Peering through the lenses, I could see structures and signals that were otherwise invisible, and watching the data appear on the screens felt like uncovering a hidden layer of the world.

Mentorship and Guidance

The guidance from my mentors made the experience even more engaging. They explained each procedure with patience and energy, often providing real-world examples to make complex concepts easier to understand. They encouraged me to reflect on unexpected results and ask questions, helping me connect the techniques to practical applications in ultra-low toxin detection and materials science. Their enthusiasm made the lab feel welcoming and approachable, even when experiments did not go as expected.

Beyond operating instruments, a lot of the work involved careful observation and documentation. I recorded the color changes, measured particle sizes, and noted irregularities, comparing them to the model experiment. Even small differences in preparation, like how I added reagents or stirred the solution, were magnified at the nanoscale. It was fascinating to see how theory translated into tangible results, and how the same principles could be applied in different ways depending on experimental choices.

Even with my nanoparticles not matching the ideal model, the process of experimenting, troubleshooting, and observing kept me engaged. Every measurement, unexpected color change, and instrument I learned to operate added a layer of understanding that went beyond theory. By the end of the internship, I had experienced first-hand how advanced technology can reveal and manipulate the tiniest aspects of matter, and how precise experimentation can open doors to real-world applications in chemistry in general and materials science specifically.

Khan Academy Vietnam

When I joined Khan Academy Vietnam as an Academic Tutor, I thought I was simply going to teach science. The idea of being responsible for others' learning both excited and scared me. But once I stepped into the virtual classroom, I realized that teaching would teach me just as much in return.

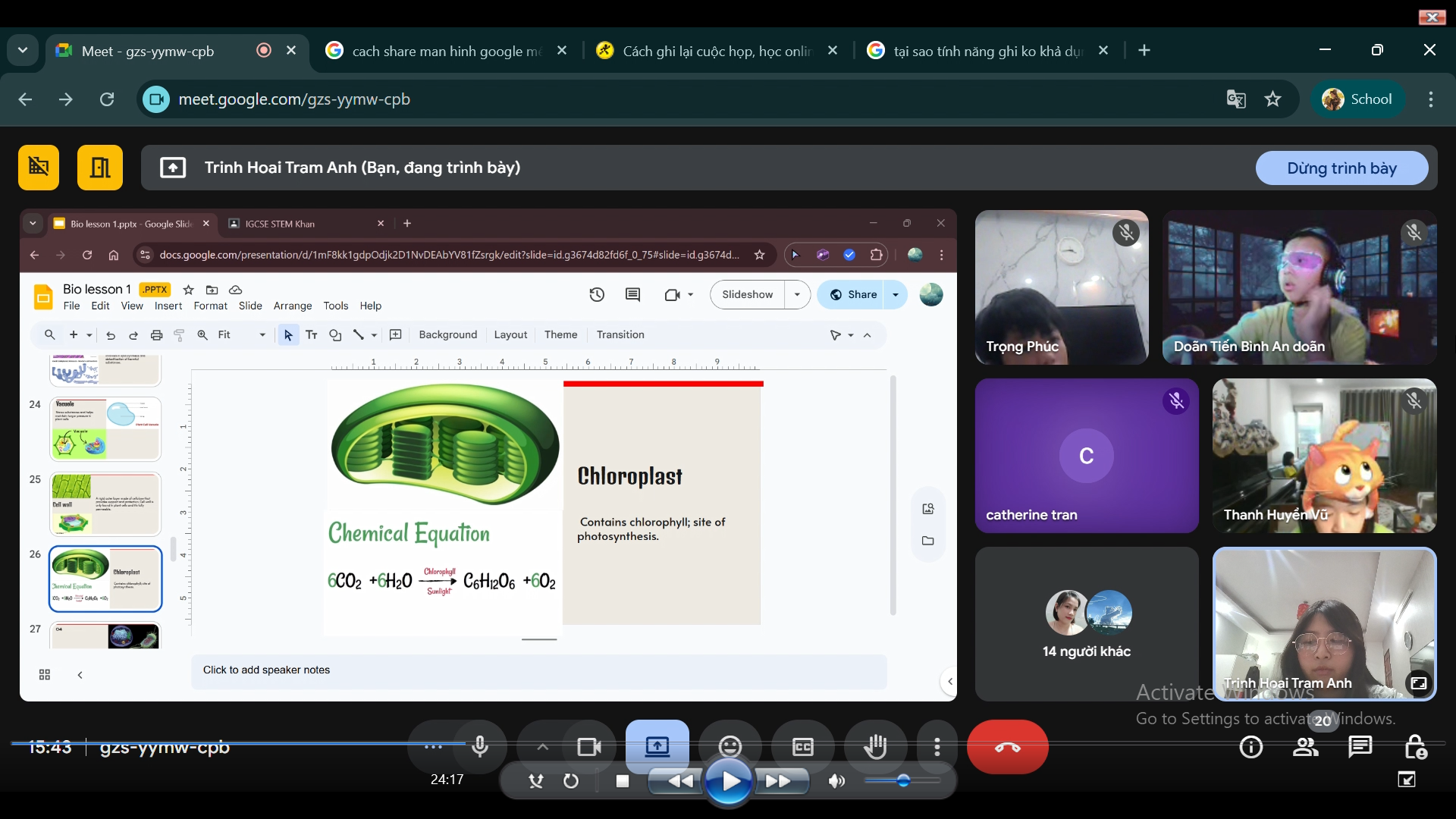

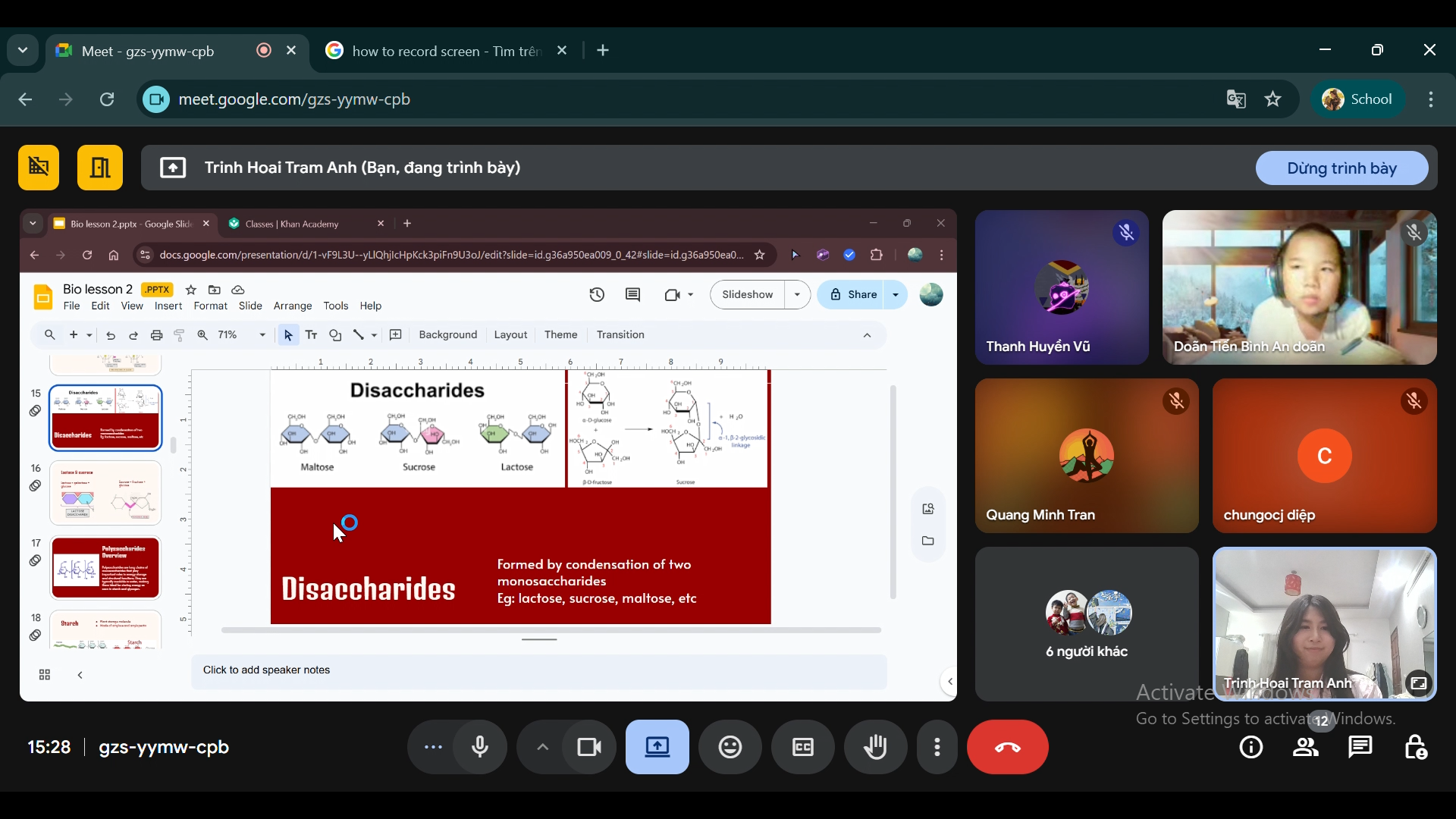

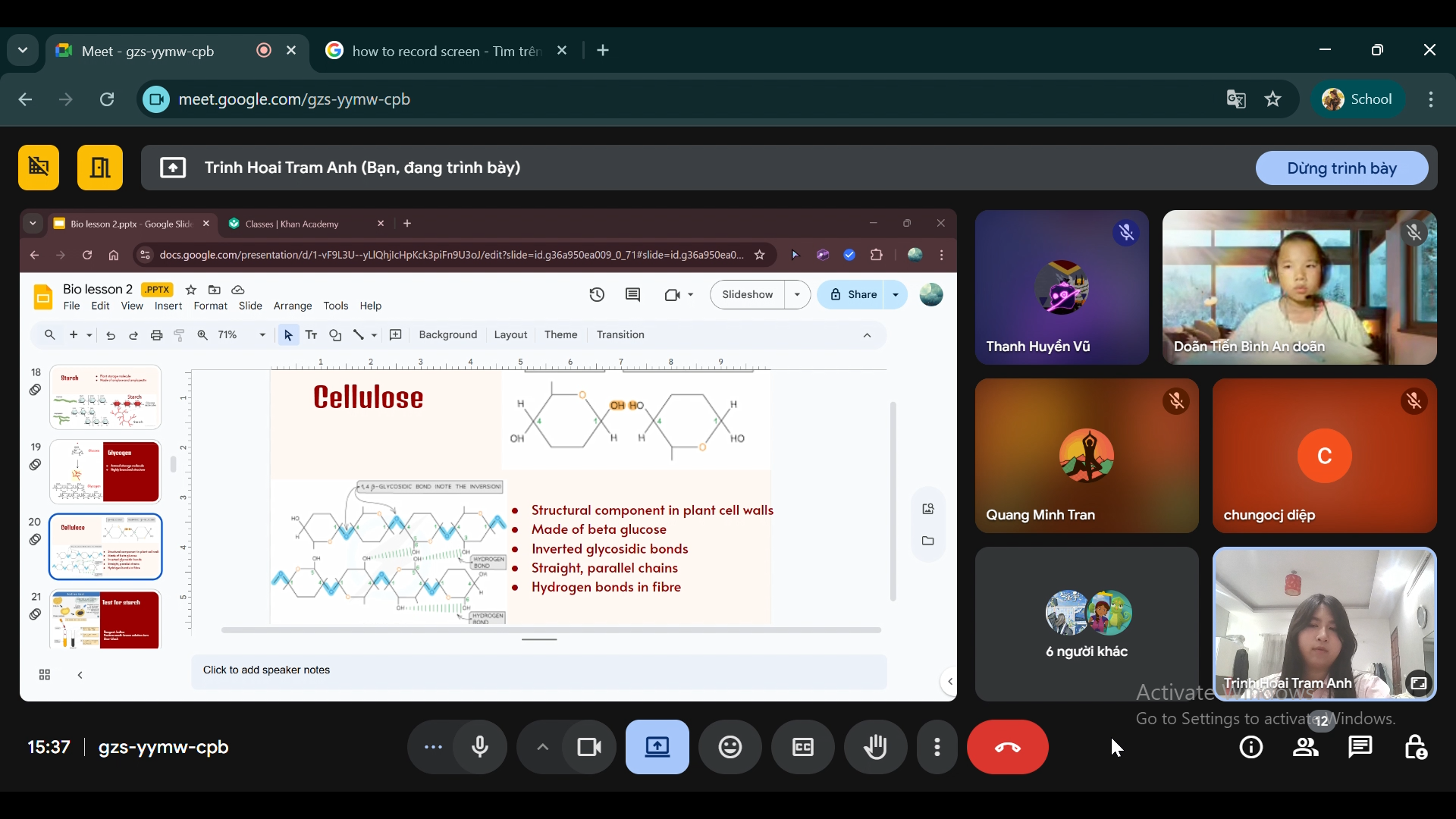

Curriculum Design

I designed a full IGCSE and AS-Level curriculum for Biology and Chemistry, creating twelve lessons that introduced sixty students to everything from biological molecules to transport in plants and animals, from chemical bonding to the foundations of organic chemistry. Each week, I taught two lessons, two to three hours each, spending almost as much time preparing as I did teaching. My slides were compact and visual, filled with diagrams, colors, and arrows that turned abstract ideas into something students could see and remember. I wanted every topic to feel like a puzzle that clicked together, not a list of facts to memorize.

Interactive Learning

Classes were never quiet. The chat box constantly flickered with questions, answers, and emojis. Students debated over which molecule was more polar or what would happen if a cell's surface area doubled. The best moments were when someone asked a question so sharp it made the entire class pause. Those questions told me they weren't just listening but thinking, connecting ideas beyond the slide in front of them.

At the end of every lesson, we played a short science game: sometimes a quiz race, sometimes a simulation or creative challenge. The energy in those moments reminded me that learning could be joyful, that curiosity itself was a kind of celebration.

Preparing for each class was demanding. I spent hours simplifying mechanisms, checking diagrams, and predicting the exact point where confusion might appear. I began to see how teaching required more than knowledge. It required empathy, the ability to step into a student's mind and think the way they do. The responsibility was heavy but deeply fulfilling. When a student finally grasped a difficult concept or stayed after class to say they wanted to study science in the future, the fatigue disappeared.

Through those months of teaching, I learned that understanding is not complete until it can be shared. Explaining ideas to others forced me to slow down, to notice the beauty in the logic of molecules and cells. What started as a tutoring role became something larger: a commitment to making science less intimidating and more human. Knowledge, I realized, grows best when it is given away patiently, clearly, and with care.